Many Acadians have fond memories of “legendary” house parties in their communities at which social dancing was a common occurrence. The kitchen was a space for family, relatives, and neighbours to meet.

SET DANCING

As Georges Arsenault explains:

In general, the kitchen was the largest room of the house and during the winter months, the warmest. Most gatherings, parties, and dances were held there. Living rooms became common in Acadian homes starting around the 1860s. That part of the house was usually reserved for special occasions and not for “soirées” where there would be a crowd of people and square-dancing. (Arsenault, 1998)

Most often, these parties took place on special occasions, such as weddings, Shrovetide (at Mardi Gras), and other special occasions, with dancing that would start after supper and often last until dawn. Kitchens teamed with as many dancing couples as the space could hold, with a local fiddler or mouth organ player providing the music.

Deacon Cyrus Gallant (1933–2013), a well known dancer, described how popular dance was in the early decades of the 20th century:

It was like there was a heartbeat in the room, and they couldn’t avoid it, they had to jump on the floor, and we can’t describe that, because you don’t see it anymore. They just couldn’t stay off the floor. (Gallant, 2012)

In her article published in The Island Magazine, Carmella Arsenault describes the central place of square dancing at house parties during Mardi Gras:

The most intense celebrations were held on Shrove Monday and Tuesday, the last two days before Lent. On Monday afternoon people would begin making visits to find a good place for dancing that evening. Once the place was chosen, it was not long before the house would be filled with friends and relatives. According to Lea h Maddix of Abram’s Village, the whole family came along and naturally expected to stay for supper. After supper the real fun began. They would start square-dancing and step-dancing, accompanied by the local fiddler and quite often someone with a mouth organ. One square dance followed another. One informant, a woman from St. Edwards, says: “We just didn’t stop all evening. The minute one dance ended, there was a group of boys waiting to ask us for the next one. I usually didn’t miss a single dance. The next day my toes were so sore I could hardly walk.”

The merry-makers would only go home as dawn was breaking. Sometimes people would catch a few house sleep before the dancing was renewed on Tuesday afternoon. Quite often they would not sleep at all and get a few hours work done before everyone gathered together again.

(Carmella Arsenault, “Acadian Celebrations of Mardi Gras,” The Island Magazine no. 4, 1978, p. 30)

You can read the full article about Acadian Mardi Gras here.

Square dancing was also done at parish picnics and festivals. Picnics were often organized as fundraisers to build new community buildings. They usually consisted of a communal meal, games for adults and children, a craft fair, band music, and traditional music and dancing.

Writing in 1980, Marie Anne Arsenault recalled how, in the first half of the 20th century, square dancing would take place during the afternoon of the picnic:

Durant l’après-midi du pique-nique il y avait des danses carrées. On construisait un “platform” avec des planches et c’était “great” pour danser. Il y avait des violoneux en masse et on s’amusait bien!” (Marie Anne Arsenault, “Les pique-niques à Mont-Carmel,” La Petite Souvenance, vol. 3, Société historique acadienne de l’Î.-P.-É., 1980)

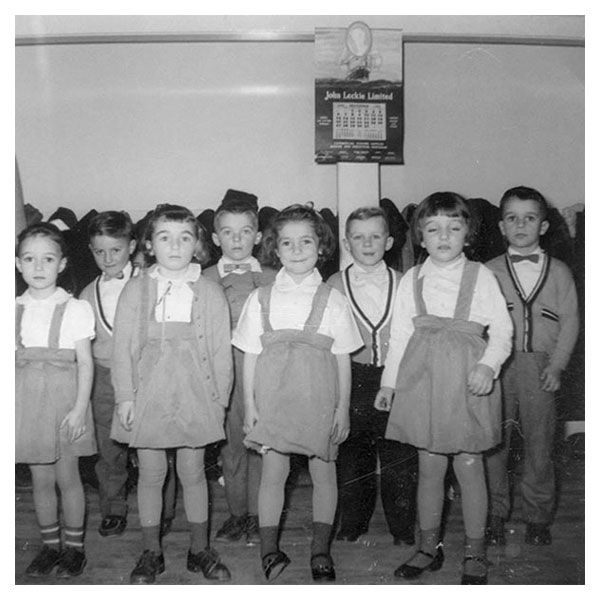

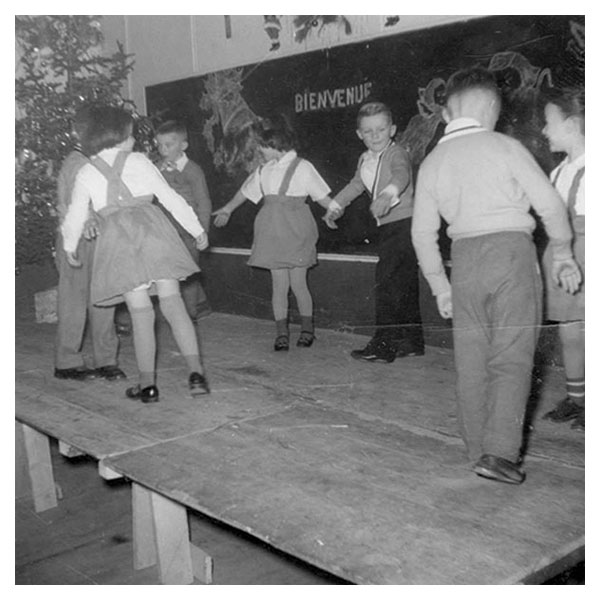

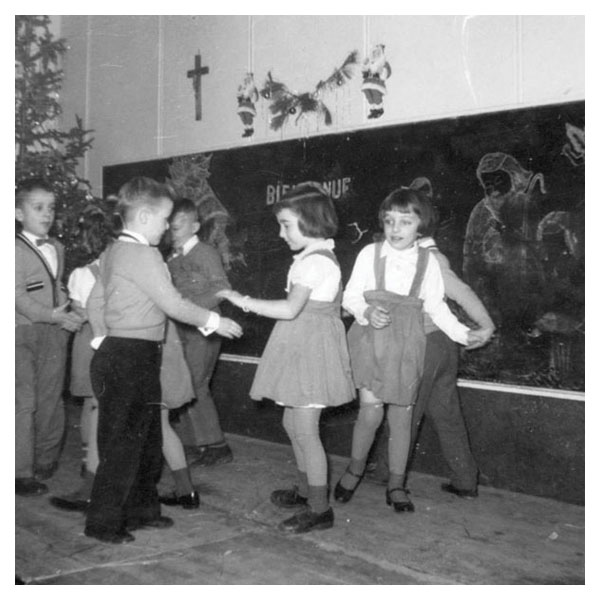

Grade one and two students at Abram-Village school getting ready to do a square dance at the 1959 Christmas concert. 1st row: Judy Savage, Gloria ( à Edgar) Gallant, Lydia (à Cyril) Arsenault, Lise (à Phil) Arsenault. 2nd row: Jacques (à Arthur) Arsenault, Léonce (à Edgar) Gallant, Eldon (à Léo) Gallant, Éric (à Ida) Gallant.

Photo taken by teacher Marie Maddix (Coll. Georges Arsenault).

LE CLUB TI-PA

Founded in 1974, the Club Ti-Pa was a French social and cultural organization (and co-operative) that served the Tignish-Palmer Road area, with the goal to preserve and promote Acadian culture in the region. In 1975, the Club initiated a number of cultural projects, including a set dancing group and step dancing lessons. The dance group – les danseurs du Club Ti-Pa – performed traditional Acadian dances in a variety of venues across the island, such as parish halls, schools, festivals, and auditoriums.

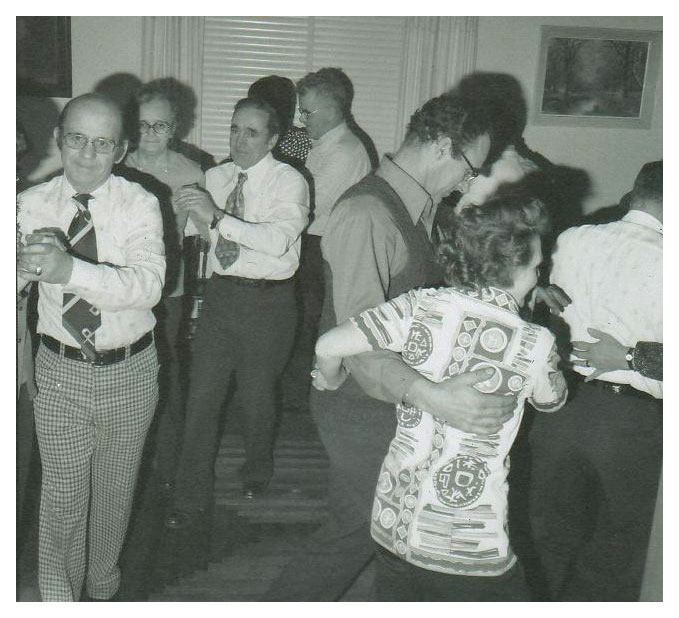

Dancers from le Club Ti-Pa perform at the Festival acadien de la région Évangéline, ca. 1980. Coll. Georges Arsenault.

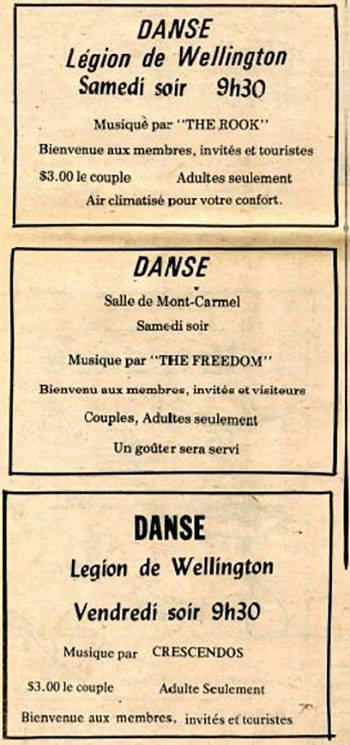

The Club 50 in Abram-Village was a popular social club that featured some traditional set dancing. Amand Arsenault recalls that the Club held dances every Saturday night with live music, as did the French Club in Summerside and other community halls where people gathered for set dancing and waltzes.

There was a marked decrease in set dancing by the mid-1950s. This was especially the case for dances that took place in houses, as social dancing moved increasingly into public venues where the traditional sets were gradually replaced by other forms of social dancing, such as “round dances,” that is, waltzes and the fox trot. In the 1950s and 1960s, the jive and other modern dances were introduce.

THE DANCES

Square dances were generally “walked,” but occasionally dancers who could step dance would do a shuffle step as they went around in a promenade figure. While certain square dances or figures were common, Deacon Cyrus Gallant recalled occasions in which dancers put new “twists” on old favourites. For example, he described a particular house party at which the women danced blindfolded around the kitchen stove – several in high, spiked heeled shoes no less – and their male partners would try to trick them by switching partners.

Le Quadrille de l’Île-de-Prince-Édouard

On July 13, 1958, Québécois folklorist Simonne Voyer (1913-2013) documented a quadrille danced at a house party hosted by Mr. Amédée Arsenault of St-Chrysostome. The musicians recruited for the party were fiddler Eddy Arsenault, age 37, accompanied by his brother, Amand Arsenault, age 30, on guitar.

She later published this quadrille as the “Quadrille de l’Île-de-Prince-Édouard” in her 1958 book, La danse traditionnelle dans l’est du Canada: quadrilles et cotillons. The quadrille, in the form of a carré simple, was danced by four couples and comprised three parts, of which only the title of the third part was known by the dancers.

Read more about the life and work of Simonne Voyer here.

West Prince Quadrille and other favourites

In 1974, Acadian historian and folklorist Georges Arsenault documented four dances from the repertoire of Augustin Gallant (1905-1979) of Cap-Egmont in the parish of Mont-Carmel, P.E.I. Augustin was a well known dance caller in the area. The first of these was known by the name “La borbis,” while the other three were identified by key figures, such as “Four hands around” and “Advance and leave your lady.” The first dance, “La borbis,” was subsequently choreographed for the troupe Les Danseurs Evangéline.

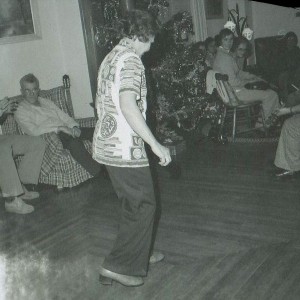

Members of the Club Ti-Pa dance a promenade figure at a house party in Saint-Louis, 1974 or 1975.

Coll. Théodore Thériault.

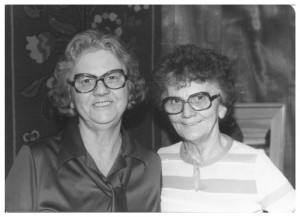

In 1980, Arsenault documented the West Prince Quadrille as it was remembered by his mother, Aldine Arsenault of Abram-Village (1916–2000), and her sister Lorette Fennessey of Tignish, both of whom were born in St. Edward, in the parish of Palmer Road in western P.E.I. As he explains, this was the only “square dance” that was danced at house parties and because it was known by everyone in the community, it was not “called.”

Aldine Arsenault (Perry) and Lorette Fennessey, 1980.

Coll. Georges Arsenault.

DANCING AND RELIGIOUS VIEWS

For many years, square dancing was looked down upon by clergy, and some parish priests prohibited dancing that involved bodily contact. Step dancing was tolerated because it was solo dancing, even on Sundays when square dancing was forbidden (Arsenault, 1998).

In 1985, Father Emmanuel Gallant of Mont-Carmel shared his memories of the relationship between priests and the public. In an article published in La Petite Souvenance, he describes the visit of two priests from outside P.E.I. for a parish retreat at the invitation of the local priest. The preachers condemned dancing as a terrible sin, announcing that those who had allowed dances in their homes may be denied absolution. Nevertheless, Father Gallant, who held a deep understanding of the importance of dance in the social life of the Acadians, recalls his and the community’s reactions to the priests’ public outcry:

Les prédicateurs avaient condamné la danse comme quelque chose d’épouvantable, disant que ceux et celles qui avaient permis ces danses dans leur maison pourraient se voir refuser l’absolution. Une dizaine de femmes furent vraiment troublées dans leur conscience. Tout le monde parlait de cela, et je me rappelle des réflexions de mon père à ce sujet: “Le Saint Roi David a bien dansé devant l’Arche d’alliance”, et il ajoutait: “Quant à moi, je ne fais certainement pas de mal dans ces danses carrées ou quadrille, car la seule chose à laquelle je pense, c’est de ne pas me tromper.” Plusieurs hommes sont allés voir le cure qui était alors le Père Théodore Gallant, natif de Baie-Egmont. Le dimanche suivant, le cure annonça en chaire: “À l’occasion de certaines noces j’ai vu moi-même les danses qui ont lieu dans la paroisse, et comme prêtre, je ne vois aucun mal dans ces danses. C’est un moyen pour vous d’exprimer votre joie, et vous diverter. Alors vous pouvez continuer à danser comme cela.” (Père Emmanuel Gallant, “La Vénération des gens à l’égard des prêtres,” La Petite Souvenance no. 13, 1985)

Oral history in the region suggests that the practice of seated foot-tapping (podorhythmie) emerged in response to restrictions imposed on music-making and dance by the Catholic Church (Forsyth 2011, 80-83; Ouellette 2005, 33), however, as Father Gallant’s memoirs suggest, there is little historical evidence to suggest that this was the case in the Acadian communities. It is more likely that the practice came about due to a lack of accompaniment instruments, such as the pump organ, piano, or guitar, and through increased exposure to a similar practice in Québécois traditional music. Nevertheless, stories about the prohibition of dance abound. One older musician recalled a story he had been told about a priest who would walk past houses and peek in the windows to ensure that the imposed decorum was being upheld and that a tradition of seated foot-tapping accompaniment developed as a way of masking percussive accompaniment to singing and mouth music. Similarly, a young musician told an account of her great-grandfather whose instruments were confiscated in New Brunswick, and so he would tap his feet to create music so that no one would see them.